In Denmark, You Can Ski On A 450 Meter Long Roof Of A Waste Incinerator

In Denmark, You Can Ski On A 450 Meter Long Roof Of A Waste Incinerator

In Denmark, You Can Ski On A 450 Meter Long Roof Of A Waste Incinerator

In Denmark, You Can Ski On A 450 Meter Long Roof Of A Waste Incinerator

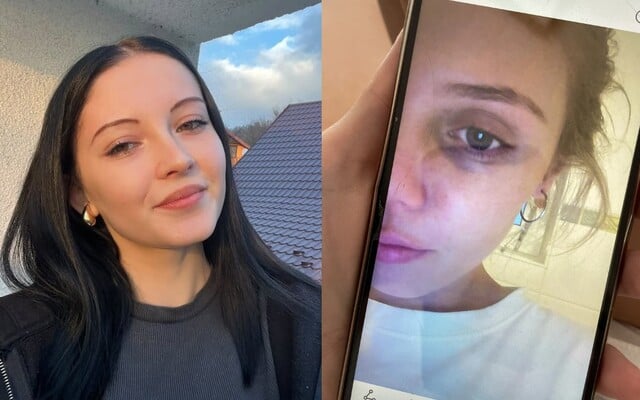

Lenka Cooked In Japan: Japanese People Work Even When They Are Sick, Doctor Gave Me 7 Types Of Medicine Because "I Have To Work"

"Everyone was quiet, everyone was just dedicated and focused on their own thing. I thought to myself: God, what kind of gangsters they are," Lenka describes her experience with a Michelin-starred restaurant in Tokyo.

If problems persis, please contact administrator.

Lenka Brindzová was born in Slovakia and has been working abroad as a cook, baker and confectioner since the age of eighteen. In Japan, she interned at the Michelin restaurant Narisawa and for three years worked at the Tokyo bakery Bricolage bread & co., which is owned by the owner of one of the best Asian restaurants awarded with three Michelin stars, L'Effervescence.

In what environment did you grow up and how was your passion for food born?

As a child, I ran around my friends, mostly acting out. Once I said to myself that I don't want to do that anymore and that I'm going to fulfil my dreams. I wasn't raised to have big dreams. However, I was born under a lucky star that guided me along the right paths.

In the eighth grade at elementary school, I knew I wanted to cook. I saw Jamie Oliver on TV and it took my breath away. I had no idea in which field I would work in, but I knew it would be gastronomy. So I went to the hotel academy and trained as a cook.

My main plan was to travel the world to gain as much experience as possible, but I didn't want to go after the best restaurants and Michelin. I wanted to visit grandmothers in Peru, Russia and China and learn to bake cakes from them.

Where did your first steps lead?

I started from the very bottom. At the age of eighteen, I went to the Czech Republic, where I worked in breweries. After two years, I traveled to Denmark, although I did not know English or Danish. I stayed there for nine years. I slowly looked for myself and realized that I never want to stop.

During your time in Denmark, you also tried an internship at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Tokyo. How did you do it?

In the Asian restaurant in Copenhagen, where I worked, I met a chef who had traveled around Japan and interned in the best restaurants. At the time, I wanted to go on an internship, but everywhere I was told that I wouldn't get anywhere without good network. These are restaurants with good names and they won't just take anyone.

I told him about my dream and he set me up with an internship at Tokyo's Narisawa restaurant with two Michelin stars.

Most chefs describe an internship at Michelin as extremely hard work. How did you perceive it?

It was an incredible experience. Everyone there was quiet, everyone was just devotedly doing and concentrating on their own thing. I think to myself: God, what gangsters they are.

I came from Copenhagen, where I worked with different cultures, everyone had a different personality. Here everyone was the same, uniformed, everyone obeyed. We compare Michelin chefs to an army - there has to be a hierarchy for it to work. Everyone has to put their ego aside and do what they have to do to achieve the best result.

It was very physically painful, I thought my legs and mind would fall off. After this internship, I said to myself that I will definitely never work in such a restaurant and I will never return to Japan.

People think that interns in Michelin restaurants do the same work as chefs. It's true?

That's a big myth. Most interns can only stand in the corner and watch – it's like entering foreign territory. The first month is reminiscent of the first year of the apprenticeship. You peel eggs, cut potatoes, put flowers in a box. After two months, they might let you do something else, but until then you only do one thing.

What exactly were you doing there?

I took care of pastries and cakes. I was lucky because they just lost their confectioner and they only had me. (laughs) We did everything by hand. When we made something from beans, we first boiled them, peeled them, made a paste out of them using a sieve, and added sugar pinch by pinch. I loved it.

How many hours was your working day?

I started at eight in the morning and as an intern I could go home at ten in the evening. However, the cooks who worked there started at 7:30 and finished at two in the morning. Although the Japanese are used to working a lot, there is also a strong emphasis on getting enough rest.

We had two or three breaks, I had more, but I didn't want to, because "you live with wolves, you howl with wolves". We confectioners could eat lunch at the table, but the youngest cooks often didn't even sit down.

When they have so much work and stress, how is it possible that they are so healthy and live to a very old age?

They are not healthy at all. Their secret, in my opinion, lies in the fact that they are taught to be strong from an early age. When they are sick or sad, they don't show it, they don't break down. They have to really trust you to open up to you.

However, the Japanese value their free time. When they are not working, they go to the spa, where everyone who visits this country should go. For six euros, you can get into the Zen garden, where you can only hear birds singing and the rustle of leaves. You lie in a stone pool in thermal water, which will completely regenerate you. Nutritious food is also very important to the Japanese.

Since they have a hard working life, the Japanese must also have better beds, mattresses, clothes. They take care of themselves. Even their toilets are an experience – a heated seat is a must, the toilet sings to you, washes you, thanks you when you leave.

Do you have personal experience with healthcare while there?

I got sick once and lost my voice. The doctor said, "I suppose you have to be at work tomorrow," and wrote me prescription for seven kinds of medicine and about three kinds of antibiotics. I said I wouldn't take it, and he said: "You have to, because you have to go to work." They probably have weaker medicines than we do, maybe that's why he gave me so many.

There are many massage disciplines in this country, chiropractic and physiotherapy are very widespread. If every Japanese does not go to a physiotherapist after the age of 25, then not a single one.

After the internship, you returned to Denmark. How did this experience affect you?

After returning to Denmark, I knew that I no longer wanted to cook in the kitchen. That I want to bake cakes and be happy. I quit my job and started looking for a new one. I worked in a restaurant for a while, where it was even worse than in Japan - I started at nine in the morning and finished at three at night. We didn't even have the 20-minute break.

After that, I changed a few more bakeries, but more and more my thoughts began to return to Japan. I had a very comfortable life in Denmark, almost all my friends, a good salary and benefits, I could travel. But I already felt that I was not growing, and my heart longed for some new experience. So I went.

Did you know exactly where you would work, or did you look for a job on the spot?

I had a list of companies where I wanted to apply for a job, and I showed it to the head pastry chef of the restaurant where I was interning. In the meantime, she opened her own pastry shop and asked me to come to her.

However, I knew it would be difficult. Although I like to do things precisely and properly, I have too wild a soul to endure not talking for 50 hours. (laughs) I didn't want to lead a typical Japanese conservative life. I worked there for a while.

In time, my friend told me that his friend was opening a bakery. At first I wanted to check how I felt about it, but finally I found out that the "friend" owns a restaurant with two Michelin stars (now three, editor's note). So I told myself that I wouldn't be picky. (smile) The bakery was called Bricolage bread & co. and I stayed there for three years.

What was the atmosphere like there?

The Japanese make sure that foreigners leave their country with the feeling that they were treated well by the locals and that they enjoyed their stay. Therefore, they treat strangers completely differently than they treat themselves. At first I didn't understand it - what's going on? Is it fake? Why can I and he can't? When I felt sick, I could always go home. They don't even ask to go home, they'd rather work sick.

Did any of your colleagues speak English?

Only one guy, the others didn't know much. I tried to learn basic Japanese expressions before - God bless you, Google Translate. (smile) I also went to a language school, because in Japan you can't really go about your daily life without knowing the language.

I had a problem, because there are three levels of politeness in Japanese - informal you, formal you and an even higher level level of formal you. In the language class, they taught me the second level, but in the bakery everyone spoke in the first level. I was confused by it. I was afraid that when an older person approached me on the street, I would talk to him in the style of: "Hey, what's up homie, what did you have for lunch today?" (laughs) It was difficult to guess what level of politeness was correct.

What should we imagine under the term Japanese bakery?

Bakery is a fairly new term in Japan, brought from France. The Japanese are great at taking something from another culture and refining it. They want it to be very authentic. I can't say that I baked Japanese bread, because there is no such thing.

It is a French bakery, but every product must be made from Japanese ingredients. We went to buy directly from farmers, we also had Japanese wheat, which is very rare, because they don't have suitable conditions for it. I loved their sugar the most, which is probably the best in the world - you take it and it changes your life forever. It tastes like Muscovado cane sugar, but three times more intense.

What was the most important thing you took from their culture?

Try to do everything to the best of your ability and have respect for every human being. Everything has its meaning. Don't be too hard on yourself. Many people perceive the Japanese as a cold nation because they do not show their emotions. I think it's not entirely right or comfortable not to show them, but it will teach you a deeper empathy for the other person.

If problems persis, please contact administrator.