Robert Vano, a world-renowned fashion photographer, who became famous for his black and white portraits, male nudes and especially photos of models in the most famous fashion magazines such as Harper's Bazaar, Cosmopolitan and Vogue.

His parents thought he would be an electrician, but he always wanted to be a photographer. Robert Vano (1948) comes from Nové Zámky, a town in Slovakia, and when he thought that he would be taken to war after graduation in 1967, he emigrated together with his two friends to a refugee camp in Italy and from there, to America.

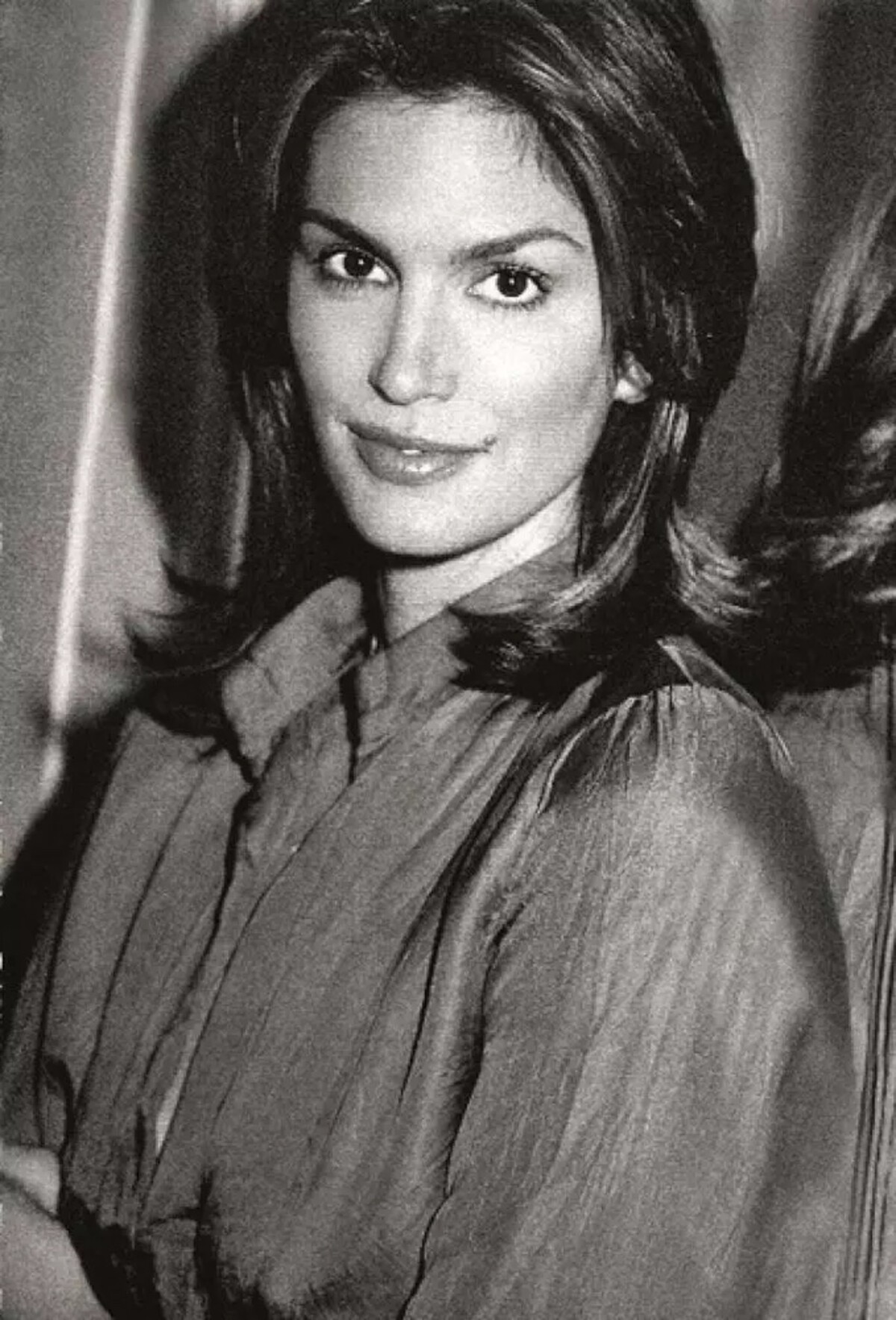

For the Americans, 19-year-old Vano was a minor, so he ended up in an adoptive family from Philadelphia. He worked as a dishwasher, later as a hairdresser. This job opened the door for him to fashion magazines such as Vogue, Harper's Bazaar or Cosmopolitan. He photographed supermodel Cindy Crawford and partied with Andy Warhol and the Rolling Stones at the legendary club Studio 54.

Today, he organizes workshops for young photographers, and if you want to become a photographer, you should definitely have your priorities in order.

"Today, the children at the workshop have a phone for a thousand euros and they haven't bought an exposure meter, which every photographer needs. When I ask them why they don't have it, they say it's expensive. The exposure meter costs three hundred euros, the phone one thousand euros. I always tell them if they want to be photographers or operators at Vodafone," he says.

Do you think that your emigration in 1967 was fate? How do you look back on it?

But this is interesting, no one has asked me that yet. When I was 14 years old, I went to the fair with my school in Štúrov. A gypsy woman had a table and a guinea pig there, I had her tell my fortune. She let the guinea pig pick out a piece of paper, there were various things on those papers, I don't remember them all, but there was one sentence. You will go through a large puddle. I thought that the largest puddle I would cross would be the Danube (laughs).

Did the desire to become a photographer also play a role in this?I wanted to be a photographer, my father bought me a camera. They told me at school that it is not a profession for boys. But there was nothing to even take pictures of, there were only funerals in Nové Zámky. What attracted me was that everyone told me I couldn't do it. I saw in the cinema that it is possible in the West. When they came to our school in the last grade and all the boys were taken to the war, I was supposed to go too, because they didn't accept me to college.

That evening we decided to leave. Today you have many options to choose what you would like to do. I didn't have them, I could have been an electrician or a miner. That would be easy, but I wanted to be a photographer.

How was the departure, were you afraid? Did you run away as children, did you think about what might happen to you?

I have that fear more now, I wouldn't go anywhere anymore. There was no information, now you click a couple of times on your phone or computer and fear is lurking everywhere. We were naive children, we thought that everything was like in an American movie. After leaving I didn't have any fears anymore because after adopted by a family, they take care of you, they find you a job. If they were to put me on a plane, I would just get off at Kennedy Airport and not know where I was going, it would be different.

The fear came again when I started taking pictures - the fear of whether I would make a living from it, whether I would succeed. When I worked as an assistant for photographers, they were always old men. My favorite photographer and teacher, Mr. Horst, told me that if I don't have a wife, family, labrador, cottage, car, drone, I will always have enough to buy bread and rolls.

Did you feel comfortable in your American adoptive family?

In that camp, when I learned that I would go to my family, I was a little afraid. I ended up feeling quite comfortable with them. But everything was different, it was a huge city, I came there from Nové Zámky. The 60s ruled, hippies, drugs, discotheques, Rolling Stones. It took me two years to learn to speak English. From the beginning, I communicated with my peers who were also from that camp like me.

Many people graduate from photography school and work as taxi drivers. No one will tell them, go as far as the eyes can see.

You partied at the legendary club Studio 54. How do you remember those times?

Studio 54 worked for two years, we went not only there, but to every disco. Then they closed it because it was said that the owner was selling drugs. Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles, Mick Jagger partied there. We were all the same age, back then these stars weren't icons for us. The icons for us were those older than Marlene Dietrich, Salvador Dalí, they also went there.

It used to be that everyone went there because it was so talked about. Until then, clubs were divided according to who could enter. There were clubs for blacks, whites, women, men, warm. Everyone could go to Studio 54. Of course, you had to look "like someone" and then the security guards at the door let you in.

How did you function at work, for example? It was a crazy period of drug-fueled partying.

I partied whenever I could, but I worked every day. We went to discos mostly on the weekend, but sometimes also in the middle of the week. If you didn't work in a factory, but as a hairdresser, dancer, photographer, you needed an agency.

You can't say no, because then they don't have money from you. In America at that time, every minute cost 30 dollars. My agency told me that I have to say yes to everything, even if it doesn't always suit me. If someone said no, they already had you fixated on not being sent anywhere because you 'never can'.

It is said that Andy Warhol approached you in Studio 54 to ask if he could take a picture of you in the toilet. Do you have that photo?

Yes, he took a picture of me in the toilet. Unfortunately, I don't have the photo, when I returned home after the revolution, I brought it to a lady in the Czech editorial office, where I did an interview. I said that when I come back, I will pick it up. After returning, there was neither the magazine nor the lady.

When did you start to believe in yourself as a photographer?

I still don't believe in myself (laughs). I recently saw an interview with Tarantino about the moment when he received the Oscar. They asked him what film school he went to. He told them that he didn't go to any school, he went to the cinema, and that's why he won the Oscar. I didn't go to any school either. There they always said that photography is not a profession for boys. You don't believe in yourself at the beginning, because here you are taught everything differently. At home, my father used to say that life is hard. I now say that life is what we make it. He said he it was hard, so it was.

Did it help that you left young?Yes. Everything was difficult at home. Father kept repeating, you have to work your way up slowly and gradually. In America it was completely different. There, this method was said to be an old theory of Maria Theresa from Europe. In America you have to start at the top and stay there, there is nothing else. In America in those years, we met famous people, everyone was young, enjoying themselves, nothing seemed impossible. There were only two female photographers in New York at the time, all the photographers were men, so I thought I could do it too.

How long did it take before you could take on the first cover?

Of course, you don't start out by being given the cover of Vogue or Harper's Bazaar right away. It started with me taking pictures of new shoes for the window for $20, of belts, pictures of new people for a modelling agency.

I got my first cover after 14 years in America, I was 40 years old. I went to Rome where there was a parade on the Spanish Steps. You took photos of all the dresses and got the opportunity to take photos not only for the fashion story with the model, but also for the caption. When it was over, we went back to New York, where I saw billboards of Cindy Crawford at the airport. I bought a magazine and it said Robert Vano under the photo. In that period, three of my covers were published in one month, in Italy, France and New York. That's when I told myself that my life would never be the same again, that I would be able to choose. And so it was.

In America, each minute cost $30 back then. My agency told me that I have to say yes to everything, even if it doesn't always suit me.

You teach students at photography workshops, what do you see as the biggest problem?

Schools everywhere teach the same things, but they don't teach how to become a photographer. Many people graduate from photography school and work as taxi drivers. No one will tell them, go as far as the eyes can see. Once I went to see a cooking school, the children there had textbooks from 1952, where it was written how to make hot dogs.

I always ask my students what they want to do when they graduate, as long as they stand up and answer me, they are tired. They start talking and end up not knowing if it will work out. And here's the problem, they don't know if it's going to work out, and that's why it's not going to work out.

For my first job for American Vogue, I needed a Nikon camera, because in American Vogue they shoot on Nikon. I needed two lenses, one cost 85,000, the other cost 100,000. I didn't have the money for that anymore. Someone takes out a loan for a vacation to Croatia, I took out a loan for a camera.

Today, the children at the workshop have a phone for a thousand euros and they haven't bought an exposure meter (a device for measuring exposure - it determines the light that falls on you, not that which is reflected, editor's note), which every photographer needs.

When I ask them why they don't have it, they say it's expensive. The exposure meter costs three hundred euros, the phone one thousand euros. I always tell them if they want to be photographers or operators at Vodafone.

You have worked in various fashion cities from New York to Paris. Which was your favourite place to work?

Probably in Italy. There was a lot of creative work, but the problem was money. Either they didn't pay you or they paid half and said, amore, tomorrow. In America it was great, they always paid, but there wasn't the freedom to do what you want.

The Germans were better at paying, even better than the Americans, there you worked that day and they paid you in the evening, but you had to do it according to them. Once I wanted to show my boss that I can do something else that they require of me for a photo shoot.

I started, you know, Mrs. Thompson, I think... she stopped me right away. You don't think, that's what I'm here for, you take pictures. You either do it the way they want it or you go home. In Italy, you never know how you're going to do it, and it always looks great as a result.

Could it be the proverbial Mediterranean mentality?

The photographer is most in contact with the graphic designer. A German calls you and says he wants a 300 dpi photo (the abbreviation dpi stands for "dots per inch" - "points per inch", expresses the number of dots on a certain surface, editor's note). The American wants 360 and the Italian says, love, I'm not going to sit here all day and open your photos, I have to go get coffee. As a result, when the covers come out, the Italian one looks the best. They have the best paper - the worse the paper, the worse the dpi.

Who is interesting to you? For example, are my colleague and I interesting enough for you to take a picture of us? Or is that not your style?

I have never approached anyone, saying that I would like to take their picture. I'm afraid of rejection, if someone told me no, I wouldn't ever take photos again, I'd just cook (laughs). That's why I go to the agency - I don't have to meet the people I want to photograph. It is much better for me to go to the agency, I say what I want, they show me a set of cards and I choose. I would never approach anyone on the street.

You were creative director for the Czech version of Elle magazine for seven years. Do you still follow what's happening in the fashion world?

I don't know anything anymore, I'm not in it anymore. Now I like to cook, so I buy Apetit magazine, I don't buy any fashion magazines. I'll look something up on the internet. You will know more about that because you are in the action.

I don't know if it still works like, when Anna Wintour says we're going to wear blue, everyone listens to her (laughs). Everything is different now, the brand was always named after the owner, and the owner was there. It was always Versace, Armani. Now I feel like they change creative directors a lot, maybe because of money. There are few new ones as well known as there once were. Calvin Klein made one t-shirt and it was instantly famous, they never went anywhere else.

Do you ever regret returning to Europe? Have you ever wondered what it would be like if you never left New York?

I don't regret anything, we all have "up and down" situations in our lives, you can't change only what you don't like. By emigrating, I was convicted of treason. I have American citizenship, if I regret it, I can go back at any time. I'm not going anywhere anymore, I have a tomb near my apartment (laughs). I love Prague, everything is close here. I never had big plans. I'm very happy, looking back, that I made a living doing what I like and it's my hobby.