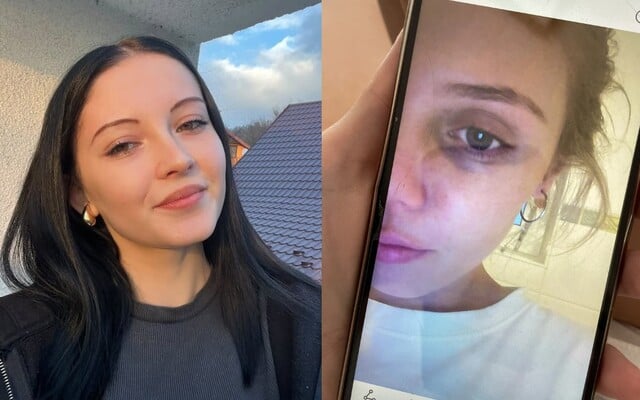

The Witch Hunts Were A War Against Women That Continues To This Day

The Witch Hunts Were A War Against Women That Continues To This Day

The Witch Hunts Were A War Against Women That Continues To This Day

The Witch Hunts Were A War Against Women That Continues To This Day

Explaining Female Hysteria: A Wandering Womb Eager For Sperm Was Supposed To Drive Women Crazy

Women with a wandering uterus, demon-possessed witches or "too emancipated" women. The diagnosis of hysteria.

If problems persis, please contact administrator.

The word hysteria comes from the ancient Greek word "hystera", which means the womb. It is in this etymological play that is the reason why hysteria was associated mainly with women. And their restless wombs.

The ancient Egyptians were the first to describe hysteria in the Kahún Papyri from 1900 BC, which, as one of the oldest surviving medical documents, record a number of cases of strange behavior among adult women. According to the interpretation of the doctors there, the cause was supposed to be the movement of the uterus, which in their imagination was a freely moving organism pressing on the diaphragm, which caused breathing problems. Therefore, they had to invent a number of all kinds of (even impossible) medicines to settle the restless womb. It often involved putting scented substances on the vulva and sniffing or swallowing foul-smelling substances, which was supposed to return the organ to its proper position.

Ancient: The womb is sad because there is no baby in it

The Greeks also adopted the idea of a migrating womb. They too chose either fragrant or foul-smelling substances as treatment. However, they saw the most effective medicine in marriage. Behind everything was supposed to be the lack of a "normal" sex life, love and, above all, babies.

The famous Messenian soothsayer and physician Melampus spoke of women's insanity as the result of poisoned wombs plagued by a lack of orgasms and "uterine melancholy". The Greek philosopher Plato in his work Timaeus claimed that the womb is sad and unhappy if it does not unite with a man and new life does not grow in it. "The womb is a living creature desiring procreation. If it remains infertile for too long after puberty, it is severely agitated, wanders in the body and cuts off the airways, obstructs breathing and brings the sufferer into extreme anxiety, besides causing various diseases,” wrote the philosopher. He meant that the uterus is desperately wandering around the body trying to find sperm. It doesn't succeed, and that's why it troubles the woman.

However, the most famous physician of antiquity, Hippocrates, was the first to use the term hysteria. He too believed that the disease consisted in the uncontrollable movement of the uterus. He attributed the cause to poisonous bodily juices which, due to a lack of sex life, had never been expelled. Simply put, with childbirth comes a cleansing. He believed that a woman's body is - compared to a man's - cold and moist, and therefore also susceptible to the putrefaction of these juices. But he went even further, according to him, virgins, widows, unmarried or infertile women had a "bad" womb. According to him, not only were their wombs supposed to travel around the body, but at the same time they released toxic fumes that caused shortness of breath, tremors, dizziness, paralysis, anxiety, and "emotional" behavior. Therefore, according to him, even these women should not resent sex. Within the limits of marriage, of course.

Similar theories were also developed by ancient Roman doctors, for example Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Aretaeus from Cappadocia or Soranos from Ephesus. Even Galen deviated slightly when he denied the ability of the uterus to "migrate". He also said that men can also suffer from hysteria - especially those who observe celibacy, withhold sperm and thus do not give free passage to "impure" fluids from the body.

Ideas about the demonic womb formed the basis of the medical concept of hysteria, which influenced medicine for millennia. And according to Greek mythology, hysteria was even at the origin of psychiatry.

Medieval to Modern: Hysteria as a Sign of Devil Possession

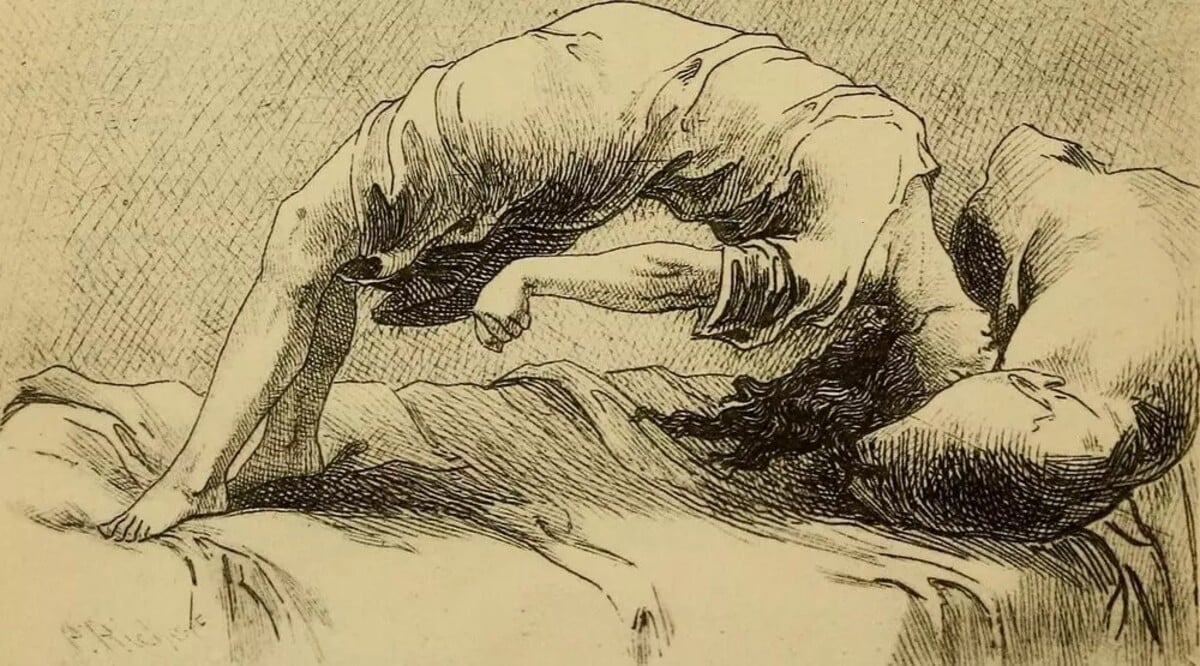

The Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern age began to divide psychopathological phenomena into natural and unnatural. Mental illness was seen as a manifestation of innate evil, which is a consequence of original sin. Hysteria was often associated with supernatural and demonic forces, and women were thus commonly accused of witchcraft. As Mark Micale points out in Approaching Hysteria, the hysterical woman has been seen alternately as a victim of bewitchment to be pitied and a soul mate of the devil to be despised.

In addition to a new diagnosis, the new era brought corresponding treatment procedures. Patients moved from hospitals to churches, and instead of scented vulva wraps, they received only prayers and exorcisms. With the demonization of the diagnosis also came the widespread persecution of sick people of any kind, as the witch craze was at its peak in continental Europe.

Only the alchemist, astrologer and physician Paracelsus included hysteria among mental illnesses. He rejected the idea that diseases were of demonic origin, but he too believed that an unhappy and cold womb was behind hysteria. Other doctors throughout Europe also emphasized that the disease should not be viewed from a religious or even a magical point of view.

Seventeenth century: Autopsies of hysterical patients

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the French physician Charles Lepois came up with a revolutionary argument: the source of hysterical attacks is not the womb or the soul, but the head. The female body was no longer such a mystery, for example, it was known for a long time that a female orgasm is not necessary for conception and that menstruation occurs independently of erotic excitement. But for most of the century, the female reproductive system was still viewed as inferior, less perfect. As Sander L. Gilman states in his study, the female body was merely "a pathological inversion of the normative male." In other words, the sick opposite of men who were considered to be the right sex.

Most physicians combined their knowledge of anatomy and physiology with religious, astrological, and astronomical ideas when diagnosing and treating hysteria.

Nevertheless, Lepois's arguments resonated with the medical community, and so autopsies of hysterical patients began to be performed. Of course, these sections refuted unrealistic ideas about uterine pathologies. Lepoise is subsequently followed by the Roman physician Giorgio Baglivi, whose elaborate casuistries (descriptions and interpretations of specific cases) led to the fact that hysteria began to slowly separate itself from an "exclusively female matter". But the biggest breakthrough was undoubtedly the creation of Thomas Sydenham's neuropsychological model, which brought progress in the knowledge of the structure and function of the human nervous system.

Even then, the women did not win. Although doctors have moved away from the wandering uterus looking for sperm, they have focused on the "weaker" nervous system of their halves. Women, they believed, were fragile and weak and could not deal with their emotions on their own without being consumed by hysteria.

Victorian era: Hysteria as a disease of "unruly" women

It is perhaps not too surprising that in the eighteenth century mankind turned again to "womb theories." The female body was apparently easier to describe using magic. Naturalists and doctors, led by Carl Linné, thus again linked hysteria with female sexuality in new classification schemes. However, as Micale points out, it was not a question of reviving ancient ideas about female sexual deprivation - on the contrary, too much sexual fervor was to blame. And actually everything that a "proper" woman shouldn't do.

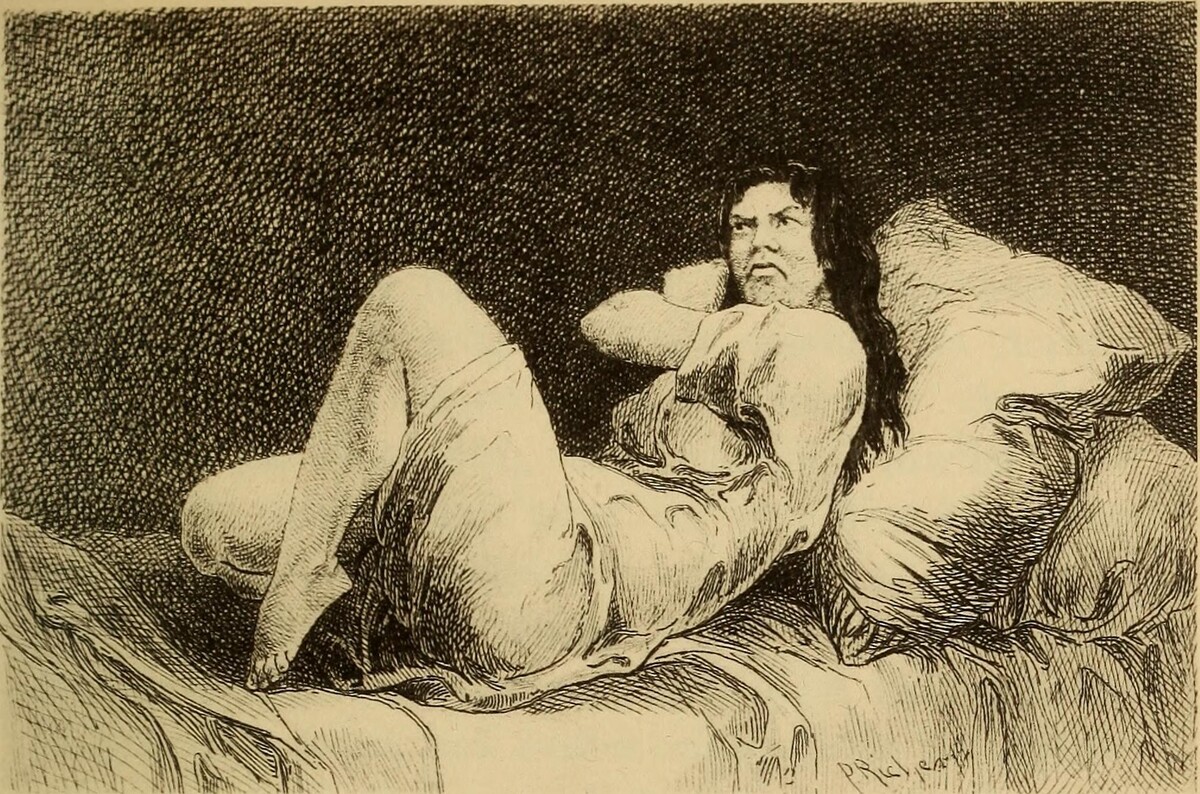

The diagnosis of hysteria had a "heyday" in the Victorian era. Almost everything that was unacceptable to the male part of society could be hidden behind it. At that time, hysteria could be caused by a number of "bad habits" - from reading novels to masturbation and homosexual or bisexual tendencies. Even now, doctors recommended the good old treatment of marital intercourse. However, some medical recommendations included cauterization, or – hold on now – burning of the clitoris.

Women were believed to have fragile bodies and sensitive minds. Therefore, they should have been extremely prone to emotional instability.

The narrator in the 1892 short story The Yellow Wallpaper, which is often interpreted as a critique of the male control of the medical profession in the 19th century, approximates that time. The main character is diagnosed with neurasthenia, a disease characterized by so-called nervous exhaustion and extreme nervousness. She was immediately forced to accept that her problem was caused by weak nerves, emotional instability and most importantly - her feminine nature. The narrator subsequently has to undergo treatment that suppresses her creativity and gives her room only to play the role of a proper wife to her husband. And this despite the fact that she herself comes up with ideas for her recovery, for example through exercise, work or contact with the outside world. But these solutions are immediately rejected with the fact that, as a woman, she is an irrational being. The heroine sinks deeper and deeper into the yellow wallpaper and dies. Like countless other "hysterical" women.

Similar procedures of "rest treatment" were advocated by a number of doctors in the nineteenth century. One of them was, for example, Silas Weir Mitchell from Philadelphia. The sick women he "treated" had to lie motionless in bed, often having to defecate in the supine position and avoiding any intellectual or creative work. Mitchell was actually the doctor of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who wrote The Yellow Wallpaper. The writer Virginia Woolf and some representatives of the suffragettes were also prescribed his rest cure. No wonder, one of the causes of hysteria, in addition to rebelliousness, shamelessness or ambition, was also considered to be excessive education. "I am convinced that a woman's desire to be on the same level as a man and to take over his duties is a mischief, for I am convinced that her education and activities will never really change her qualities," the doctor wrote.

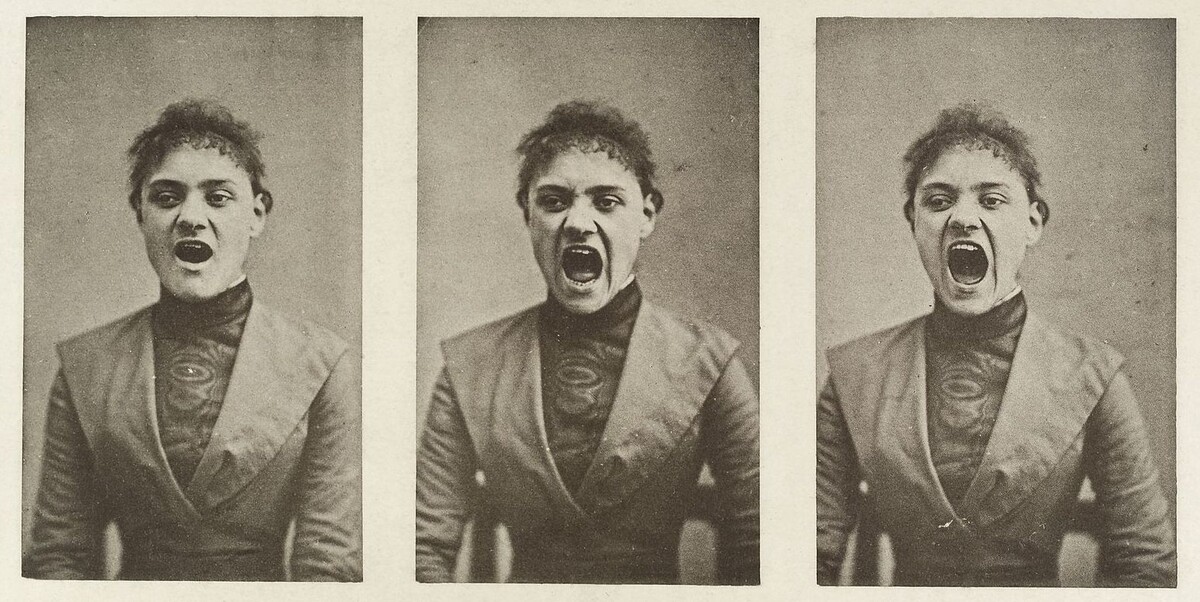

Geneviève, Rosalie, Justine and the ovarian compressor

Jean-Martin Charcot, a French physician, is most prominently associated with hysteria in the Victorian era. He dealt with hysteria from 1870 until his death in 1893. Together with his collaborators, he described the main characteristics of hysterical-epileptic seizures, often emphasizing their sexual "flavour". He used countless "hysterical" women as guinea pigs for his psychiatric research. The most famous of them are Blanche, Augustine and Geneviève, who today are referred to as the "queens of hysteria". All three women had a low status in society, were abused in childhood and then repeatedly experienced sexual assaults or rape as adults.

Charcot believed that his device called the "ovarian compressor" could cure their frequent nervous breakdowns. According to him, the ovaries were certainly responsible for their problems. If not the uterus, then what else. The compressor induced or stopped hysterical attacks by pressing on the patient's abdomen. The Charcot technique was often used in combination with ether, to which many women subsequently developed an addiction. He further "raised" his attempts when he opened the hysterical department of Salpêtrière to the public. Buy a ticket for a spectacle with female hysteria in the main role!

He not only manipulated women's bodies in a degrading manner, but also practiced hypnosis and so-called dermographism on them. In this method, he would carve different words on the woman's chest or stomach with the tip of a spade. After years of public performances and experiments, the women's seizures stopped. There is no explanation for their miraculous recovery, except that it coincides with Charcot's death in 1893, writes Laure Murat in his work.

19th Century: The Golden Age of Hysteria

Later, the Austrian neurologist, psychologist and founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud began to deal with hysteria. He did so at a time when various experts from all over the world were interested in hysteria, but they could not agree on either the symptoms or the treatment. In conversations with internist Josef Breuer, he learned about the treatment of a particularly complex case of Anna O., probably the most famous patient in the history of hysteria. The patient suffered from visual disturbances, hallucinations, partial paralysis and also had speech problems. Although Freud never met Anna O., her story fascinated him and served as the basis for the book Studies on Hysteria, which he co-wrote with Breuer.

Through this case, Freud came to the conclusion that hysteria had its roots in childhood sexual abuse, which of course led to a disagreement between him and Breuer, who did not share this view. The collaboration thus ended, but Freud continued his research. He subsequently developed the method of conversation therapy as one of the treatments for mental illness. As Micale states, Freud himself once identified Anna O. as the real founder of the psychoanalytic approach to mental health treatment. However, her condition gradually worsened, and she was eventually placed in an institution.

The number of cases of hysteria in Europe and North America declined significantly in the early 20th century. What was behind this is not entirely clear - some indicate a shift away from repressive Victorian culture, others a better understanding of neurological diseases.

As feminist historians and historians such as Laura Briggs point out, it is noteworthy that the hysteria about hysteria peaked in the nineteenth century, when women began to claim their place in the public sphere. Women wanted to get more education, build a career - and give birth less. And as if by chance, a hysterical epidemic swept the world. Hysteria was thus never just a disease. It was a systematic problem of a gendered but also a racial nature. Indeed, as Briggs mentions, hysteria contributed to a discourse according to which white middle-class women threatened the race with their low fertility, while poor women had many children. Therefore, doctors characterized white women as weak, fragile, and nervous, while describing women of color as strong, resilient, and fertile.

Hysteria was never just a disease. Behind the term lies ignorance and misunderstanding of the female anatomy, sexism, racism and an oppressive tool of control. So if you say about someone that they "behave like a hysteric", please, just don't.

If problems persis, please contact administrator.